I remember how stunned I was watching the morning news that day; the first tower was on fire because, as the announcer said, a small plane has crashed into the building. But as we were watching, what was clearly a passenger plane flew into the second tower and exploded in an enormous fire-ball. I was terrified, and spent the next few days glued to the screen to try to sort out my emotional chaos. For weeks I felt in my body the shaking of my sense of security.

But this morning, twenty-one years later - nothing. I can remember what happened and the fear that it instilled, but today these are facts, not feelings. Today, I’m not worried about terrorists or my family’s security; perhaps most surprising and disturbing, I feel none of the grief I felt then for the 2,966 people who died in the attacks. In early August, Ayman al-Zawahiri, who is called the mastermind of the 9/11 attack, was murdered by our CIA at his supposedly-safe house in Kabul, Afghanistan. Neither his death nor the arrival of this anniversary day has stirred any emotion in me, which surprises me.

Since al-Zawahiri’s death, I’ve been thinking about this lack of emotional response, wondering if something has happened to harden my heart. How do such fierce, tumultuous emotions fade to simple facts?

When my sister called (twenty five years ago now) to tell me Mom had died, Becky and I jumped in the car and raced to the hospital emergency room where they had pronounced her dead before we arrived. I approached the gurney slowly, frightened by her rigid, pale face. When I touched her cold forearm I started wailing, sounds coming out of me that I’d never heard before. For the week leading up to her graveside memorial service, my throat closed each time I thought of saying my final Goodbye to her.

I carry you in my heart is a phrase from the poet e.e. cummings. It captures my relationship with my mother in the years since her death. I’m grateful to have had a love that thought the sun rose when I opened my eyes each day, the life-long source of that soulful mother’s milk that nurtures me even now. But I no longer think of her very often, and when I do there’s very little emotion attached to the thought. It seems wrong even to write this, but the truth is that I seldom miss my mother.

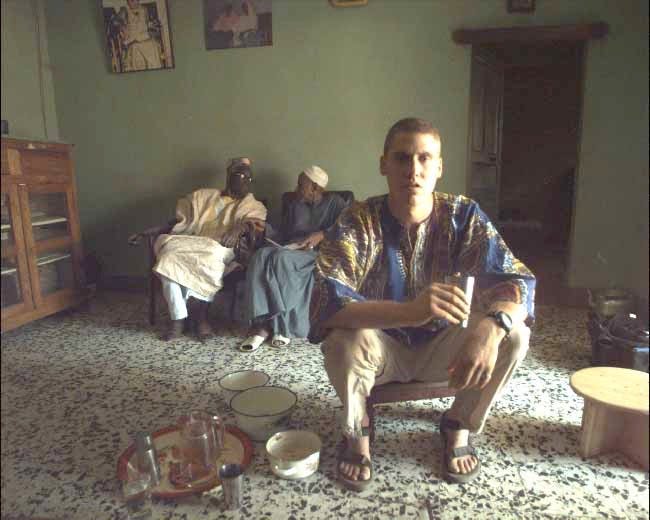

On Friday evening, January 7th, 2000, Becky and I got a phone call from the Director of the Peace Corps telling us that our younger son, Jesse, had been killed that morning in a collision between a truck and the African bush taxi he was riding in. Like my reaction to touching my mother on the gurney, sounds came out of me that were so primitive, so gut-wrenching that I had trouble catching my breath. His death set loose torrents of grief that left us completely depleted.

We battled for years with the dark void caused by our loss of him. His death badly damaged the faith in God we’d grown up with, and led us both to a firm conviction that life is uncertain and no one, not even God, is coming to rescue us from the unexpected.

But now? I think about him, of course; it would be difficult not to. Photos of him surround us; his brother and sister and some of our relatives repeat both new and well-worn tales about him, which we call Jesse Stories. When he was in high school, he and his first girlfriend made Paul Simon’s song America their song; now when I hear it, it touches that place in me where music has its own way of remembering, and I tear up. And most unavoidable, his now-seventeen-year-old nephew, his sister’s older son and our beloved grandson, is named after him. So he is forever present.

But I no longer ruminate about him while trying to fall asleep, I seldom ache at his absence, and frankly I don’t think of him very often. Whatever residues of grief remain in me, I carry them now as facts, not feelings. At an emotional level, I seldom miss him.

Now, when I think of my mother or Jesse’s tragic death it’s like pressing my thumb on an old bruise; if I press hard enough for long enough, Ouch!, there it is. But it takes a lot of pressing to feel anything at all like the pain of the past.

Maybe some of my diminished grief comes quite naturally with the passing of time. My mother’s death in the mid-1990s, Jesse’s death in 2000, and even 9/11 in 2001 are all more than two decades in the past. Also, I was in my late fifties and early sixties when these tragedies occurred; I turned eighty-one this past June. Perhaps growing old dulls even these memories of profound grief.

And perhaps these awful moments in my history have lost their emotional punch because I did such a good job of grieving. Maybe the eruptive crying, the dark void I stared into for so long, the rage at what each death stole from me were so deep and thorough that I was able to move on from them. Maybe I was successful in working my way through even these horrific losses.

It took a long time with Jesse. His death was so life-altering for Becky, Shannon, Brendan and me that we had to learn to live with this damage to our hearts where he’d been ripped out of each of us. Even when his namesake nephew was born nearly six years after his death, it was difficult to transition to having another, different Jesse. For two years or more, Becky called him Bubba because, as she said, I already have a Jesse. But the wound began to heal, the pain subsided, and as with my mother, we found a place for him in our memories that was no longer so raw.

And I was fortunate not to have to grieve by myself.

My mother had surgery two years before she died, which revealed an inoperable aneurism on her abdominal vagal artery, which we never told her about. In the two years before it erupted, our family surrounded her, listened to her oft-told stories, bathed her in affection. When she died, none of us cried alone. My sisters and I called often, always expressing our gratitude for her, telling familiar stories from our childhood and hers. This constant remembrance of gratitude for her slowly moved our sadness to the margins of our memories; now we carry her in our hearts with the same calm delight that she brought to us throughout her life with us.

In the week between Jesse’s death and his memorial service, Becky, Shannon, Brendan and I clung to one another in our desperation. Our families arrived the morning after he died, surrounded us, cried with us, became our consoling companions in the darkness. We never answered the door or poured a drink or answered the phone or prepared a meal; our friends, many of them from our faith community, did all of that. Day after day, they were there early in the morning and more than one of them would stay until we said goodnight and went upstairs; only then did they let themselves out, only to return again early the next morning

.

Luckily, we were a year into marital therapy when he died, working our way back into our relationship after a seven-year separation - healing a different kind of wound. When we met our therapist the Friday after Jesse died, he’d already heard the news and opened his office door with tears in his eyes. For weeks, we unpacked our grief with him as he allowed us whatever space we needed for our rage and hopelessness and unrelenting sadness. Week by week in his office, Becky and I stitched ourselves to one another in our common grief, turning what is so often a marital disaster for couples into a secure knowledge that we had one another’s backs.

My mother and Jesse live in the stories we still tell about each of them and in the pleasures of life with them I’m reminded of each time we share their stories. But I’ve moved through my once-torrid grief and slipped into a place that is no longer ripe with pain. I carry them in my heart in a peaceful, grateful way that is dominated now not by grief but by gratitude.

I’ve missed your ‘thinkings’ and SO GLAD to read you again. —Gordy