Thanksgiving week through early January is, on my calendar and in most American’s imaginations, one extended holiday season. I still get caught up in this turmoil of over-eating and over-spending, but for many years, I've haven't experienced this as a season of celebration. My mood through these weeks is best summarized in the opening line of Shakespeare’s Richard III: the winter of our discontent. Even after twenty-three years, this somber mood arrives like the season’s first chill as sadness once more lowers the temperature of my soul.

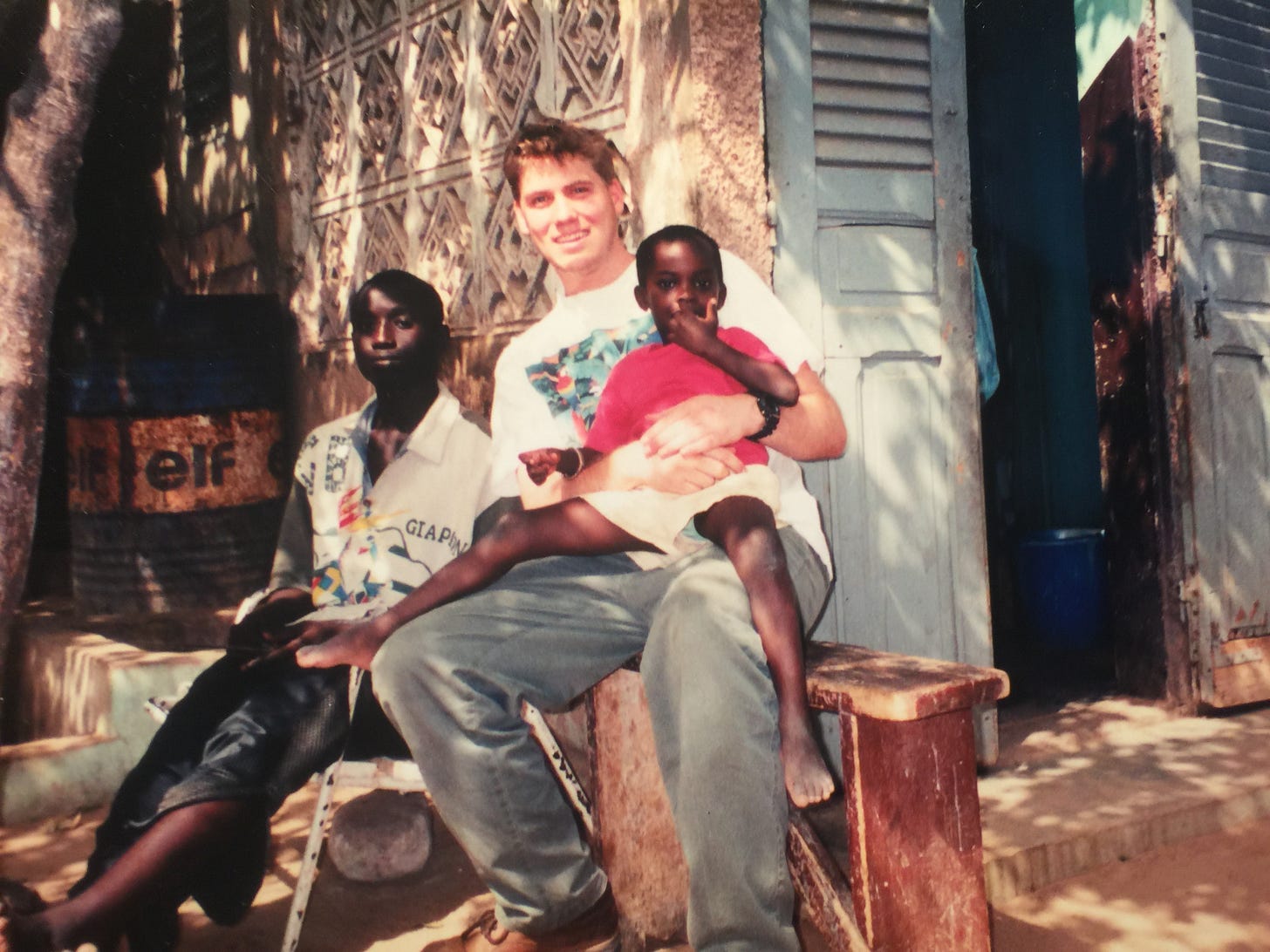

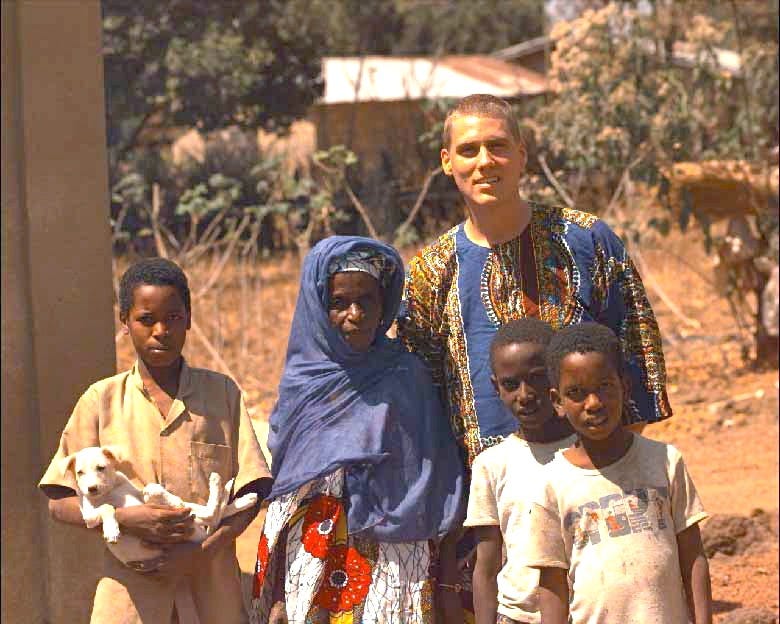

In the fall of 1999, our younger son, Jesse, was in his second year as a Peace Corps volunteer in Guinea, a West African country that was then the sixth poorest country in the world. In early November, he felt a small, hard growth under his skin and since there were no adequate medical facilities in Guinea to do the necessary diagnostic tests, the Peace Corps flew him to Washington, D.C., to be examined. The results were benign, but they put him on meds and wanted to see him ten days later. Lucky us! Our extended family was gathering in San Francisco for Thanksgiving at our daughter’s home, so we bought him a ticket.

We hugged and kissed him, grateful for the assurance that comes from touching someone even after you learn that the news is good. We ate and drank for three days, listened to his stories about Africa, and on Saturday morning said Goodbye when he left to fly back to D.C. for a final visit with his doctor, then on to Guinea.

Six weeks later, at dinnertime on Friday night, January 7th, 2000, Becky and I got a phone call from the Director of the Peace Corps, telling us that Jesse had died that day in a horrible traffic accident, riding in a dilapidated bush taxi from the capital city back to his rural village. Ever since that phone call our lives, and the lives of our two other children, their families, and others of our friends and his, have divided time into BEFORE JESSE DIED and AFTER JESSE DIED. Although we now live a rich and happy life together, there has never been and will never be that closure which people who have not experienced such a tragedy think possible. When this holiday season comes, the temperature in my soul drops once again to the now-familiar winter of my discontent.

Over the two-plus decades since he died, dealing with my grief at the loss of him has done to me what eighteen months in Guinea did to him: it’s pared me down. I learned the phrase from him in late night conversations when we visited him a year into his stay there. He lost thirty pounds in his first six months from a diet limited to rice, various sauces, and warm loaves of bread baked each morning by the woman in the hut next door. But more important, it pared him down to essential questions about his life, and to a radical commitment to dealing honestly with whatever he discovered.

He quickly came to realized that, despite his initial fantasies of having a large impact, he would have only minimal influence on his village. There was too much for villagers to do just to pump water from a common well, farm the rocky hillsides for a few vegetables, and cook over open fires in their conical thatched huts. The children to whom he was supposed to be teaching math and English were mired in this same routine of survival tasks which regularly called them away from school.

The other thing Jesse couldn’t avoid, in addition to losing weight and re-calibrating his impact on village life, was paring himself down. Alone in his small room every night, he dove into questions he’d never fully explored. He learned early on that in circumstances where eating was the first task every day, the right clothes, the right appearance, the right grades, the proper friends, his favorite foods – those choices that had shaped his life before Guinea – were, to use his explicit language, shallow bullshit. As the months passed, he dove deeper:

Why did my birth mother give me up when I was a baby? Maybe I should try to find her when I get home, and ask her. Michelle and I want to marry when I get home, but is that just a reaction to the loneliness of being so far apart for so long? With my now-familiar atheism, I’m as comfortable celebrating Ramadan with my Muslim villagers as I was being an acolyte in the Episcopal church I grew up in. But is there anything I hold as truly sacred?

It rubbed off on me. Issues that had consumed me before his death – Do I have enough clients? Am I making enough money? Am I dressed for success? After building a five-thousand-square-foot home, is moving to a town house a sign of failure? – seemed like so much banal materialism.

And this paring down started to show up not just in my reflections but in my interactions with other people. Ten minutes before a therapy session with a regular client ended, he said something that I knew was not true; he was kidding himself or trying to finesse me, or both. But for some reason, I just nodded, said Uh Huh, and finished the session without challenging his comment. Later, I asked myself - why didn’t I respond with my honest reaction? Was I afraid he wouldn’t like me, or might not return, which could cost me some money? I returned to this thought for several nights, like Jesse in his village room. Finally, I just laughed at myself. Look, you made it through Jesse’s death, so what could possibly happen with a client that you wouldn’t be able to handle? Why do you keep silent when you know what you’re dealing with is – as Jesse would say – shallow bullshit?

Subsequent years of my own self-reflections, decades of working with individuals, couples, and kids as a psychotherapist, have driven me deeper and deeper into a search for what is real. Over time I've pared away what is comfortable in favor of whatever truth I find. I seldom make the mistake I made with the earlier client; I pretty much tell the truth now, and deal with whatever the consequences are between me and whomever I’m talking with.

Since our son’s death, my wife’s once-clear faith is no longer so transparent. We prayed for Jesse every day, to the God we grew up with whom we believed had a plan for our common lives, and whose promise is that all things work together for good. (Romans 8:28) Since that awful January tragedy, I live with the unassailable righteousness of her questions:

Where is the good in this tragedy? Where is God in this tragedy, other than absent? If this is part of God’s plan, what kind of monster is this God? For all the promises, for all our prayers, what difference did God make?

Faith is no longer a clear road ahead but a dense fog in which our next step may lead us forward on the path or leave us tumbling off an invisible cliff.

As Becky has lost her religious hope, I've lost my political and cultural hope. For myself, I admit that for the past few years I kept expecting a wise leader, respected by everyone for his/her integrity and wisdom, would somehow radiate through the fog, convince the great majority that we have enough common ground to cooperate in creating a meaningful future for all of us, and deliver us from this impenetrable fog. I’m losing such hope.

Perhaps there will be no closure to our contentious deliberations. Perhaps there will be no happy ending to our quandary. No radiant hero. No widely accepted evidence. No common truth to bind us to one another.

Living in demanding circumstances - Jesse in his village, me in my grief - pares us down. It strips back the illusion of fixing things and the mirage of happy endings, platitudes that don't hold up to reality's icy bite. We are left to huddle in fragile safety within our separate tribes, sharing a set of convictions that make us feel safe about our faith, our politics, our sense of economic justice, our parenting skills, our ways of relating to one another. Perhaps if we believe hard enough, and do exactly the right things, the fog won't blind us. But of course, in the end, it always does.

The alternative left to each of us is to have the bravery to move forward into the fog. For me, such bravery requires spending and voting in line with my convictions, and telling the truth in whatever situations I find myself, and continuing thoughtful reading and conversations with my friends to clarify my views of reality. We are not hopeless so long as we raise our voices, act with integrity, and search for and serve the truth even as we continue to live through the winter of our discontent.

Hit the wrong button-- that too, pares our arrogance down so that when we die, all that may remain is the love that alternately brings joy and grief, and combinations of those. Spring will come, my friend.

This touches my heart deeply, Rick. To be pared down: is this part of what we came here to learn? Aging and tragedy